History

It neighbors Martha’s Vineyard on the east, and sometimes a slender beach connects it to the rest of the Vineyard along the south. On a map, it looks big, with a great barrier beach hooking wide and long over the top, but the actual landmass is small, only about thirty-eight hundred acres. Chappaquiddick is as much an island of bays and ponds and inlets as it is of hills and fields and forests.

Chappaquiddick was created during the last ice age, shoveled and dumped into place by the same glacier that built up the rest of the Vineyard around 21,000 years ago. In fact the hills of Chappy, the Vineyard, and Nantucket mark the end of the line for the great ice sheet; the glacier would advance no farther to the southeast than these three future Islands, and on retreat, it would leave behind the most recently deposited – and therefore geologically newest – ground in all of New England.

The first settlers, ancestors to the modern Wampanoags, arrived from Asia and the continent well after the ice pulled back into Canada, roughly 12,000 years ago, but still long before the Islands were surrounded by water. The seafloor in this epoch was still a cold, vast, and inhospitable coastal plain, with the waters of the Atlantic Ocean lying hundreds of miles to the south.

But as the ice melted away, sometimes in explosive south-rushing torrents, the sea advanced rapidly, and by 6,000 years ago it had surrounded, from west to east, the Islands of Martha’s Vineyard, Chappaquiddick, and Nantucket. The rising Atlantic filled the shallow waterways known today as Vineyard and Nantucket sounds, separating the two larger islands (the Vineyard and Nantucket) from one another by about eighteen miles. It also filled what is now Edgartown Harbor and Katama Bay, which also separated the Chappaquiddick landmass from the Vineyard landmass by just 527 feet at the harbor entrance and about a mile and a half at the widest part of Katama Bay.

(But it’s worth noting here that Chappaquiddick isn’t always an island unto itself. A slender stretch of South Beach known as Norton Point sometimes connects the southern shore of Chappaquiddick to the southern shore of Martha’s Vineyard, and in these periods, which can last for decades, Chappy is technically a peninsula of the Vineyard. Yet great storms and tides periodically bust open this beach to the ocean, separating Chappy from the rest of the Vineyard for decades more – which probably accounts for the transitory meaning of the word Chappaquiddick: “at the separated island.” Most recently the bay broke through the beach to the ocean during the Patriots’ Day Storm of April 2007, and since then Chappy has been an island in fact as well as spirit.)

From the start, Chappy was different from the rest of the Vineyard, a wild and buffering outpost of hills but few plains, of rock but mostly thin and sandy soil. Facing north, east, and south, Chappaquiddick shielded much of the eastern half of Martha’s Vineyard from coastal storms even as it took the brunt of these gales itself. Set off by itself, a frontier in every way, the island became the home of the hardy Chappaquiddicks, one of four tribes to occupy the Vineyard and its large satellite island. The Chappaquiddicks fished from the shoreline, cleared land by fire, grew crops, whaled from shore, hunted, and quahogged in the verdant shellfishing beds of Cape Pogue Pond.

The first white colonists settled Edgartown, just across the harbor entrance from Chappaquiddick Point, in 1642. Thomas Mayhew Sr., his son Thomas Jr., and a clutch of perhaps thirty other settlers from townships near Boston were looking for an outpost of their own, an island where they could run their own affairs, both politically and in trade. Once established in Edgartown, these newcomers quickly proclaimed Chappaquiddick to be a part of their own village, and from fall to spring pastured their livestock there because they knew they did not need to build fences to keep it from wandering off.

The settlers, it must be said, brought calamity to the Chappaquiddicks, who fell victim to diseases for which they had no biological defenses, whose lands were overrun by livestock, and whose deeply spiritual lives they were called upon to forsake when Thomas Jr. began to teach them about the commandments of a Christian God. The first convert to Christianity in all of New England was in fact a Chappaquiddick native, Hiacoomes, who himself became a revered pastor, not only to his fellow natives but to the English who had introduced him to their own puritan faith.

The first of these new settlers set up homes on Chappy around 1750. With the surviving Chappaquiddicks relegated to less productive ground lying north of what is now the main road on the island, the newcomers fished the waters and farmed the land. To a remarkable and particular degree, they also took up the adventurous life of offshore whaling. In 1871, the Vineyard Gazette listed forty Chappaquiddick men who had risen to the rank of whaling master, possibly the largest number per capita of any place on earth. Among them was Captain William A. Martin (1829-1907), one of the few men of color to achieve the rank.

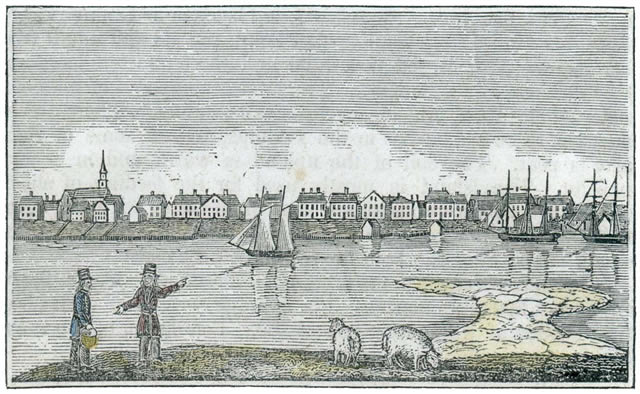

In the first years of the nineteenth century, Edgartown – which never had a large whaling fleet of its own – established itself as a seaport known for the skill of its whaling masters and effectiveness of its waterfront industries, especially rigging, ship repair, processing catches, and provisioning whalers for new voyages. Across the harbor, Chappaquiddick evolved into a place of business too.

On the Point in the early 1800s there was a large saltworks, and across the island one could find at least one boatbuilder, and a thriving shellfishery that boats as far away as Connecticut came to buy from. At faraway Wasque Point there were also pilots who braved wild seas, unforgiving shoals, and merciless currents to row surfboats miles out to schooners and whalers, where the pilots would board the vessels and guide them safely into port.

With the collapse of whaling after the Civil War, Edgartown slid into a depression from which it would take decades to fully recover, a decline that would also transform the village from a place that made its money from industry to one that made it off of leisure. But resorthood was slow to come to the old seaport. Most visitors and summer residents confined themselves to neighboring Cottage City (now Oak Bluffs), a merry town of hotels, promenades, and amusements that grew up suddenly in the postwar boom, surrounding what today is a tranquil enclave known as the Camp Ground, but which was then a spectacularly large and famous summertime meeting of converts to evangelical Methodism.

Yet Chappy, separated and self-reliant, felt the economic suffering of Edgartown less – mostly because it had never prospered that extravagantly to begin with. The ferry between Chappy and its parent town, in business at least since 1807, was nothing more than a rowboat at the end of the nineteenth century, which signifies how little commerce probably was going back and forth between town and island in this period. In the 1870s, there were as yet no summer residents on Chappy, no stores, nothing resembling a village. Just a few houses, a few farms, a meetinghouse standing bravely atop the highest, scrubbiest hill, and a one-room schoolhouse for white children and the few Wampanoag youngsters who remained.

If anything snapped Chappy forward into the modern era, it came across the harbor by barge on Thursday, July 18, 1912:

“We understand the first automobile on the island of Chappaquiddick went careering over hill and dale yesterday afternoon,” reported the Vineyard Gazette. “It was taken over on a large scow and belongs to Dr. Frank L. Marshall of Boston, who has a summer place near Joel’s Landing. We are told the frequent honks as it proceeded to the Doctor’s place so aroused some of the staid inhabitants that Gov. Handy” – William Handy, a Chappy deliveryman and jack-of-all trades who rarely left the island – “came to town to see what it was all about.”

But the first genuine car-and-passenger ferry – a scow with its own engine and helm, designed by Tony Bettencourt, the ferry owner, and considered revolutionary at the time – did not go into service until the spring of 1935, and by that point, Chappy was as fully ensnared by the seasonal demands of resorthood as the Vineyard as a whole was.

Yes, many Chappaquiddickers still lived principally off the water and the land. But now there was a bathing beach on the Point (now the Chappy Beach Club) filled in July and August with hundreds of visitors from the town, laundry trucks bounced over the dirt roads of Chappy with fresh linens for summer residents, and year-round Chappaquiddickers took on the same jobs in service of summer folks as year-round Edgartonians were on their side of the harbor.

Yet well into the twentieth century, by accident of geography and the quiet determination of residents both all-year and seasonal, Chappy remained just difficult enough to reach that it kept its outback feel. What houses there were remained few and scattered. No business district grew or spread. The one main road remained only partially paved. Forests grew over the old farming fields, but the island held on to its austere beauty – a wild, wind-blasted, tangled, gray-green unkemptness that invited all but the most inquiring and adventurous souls to almost forget that it was even there.

All this changed, of course, on the night of July 18, 1969. The following morning, a sedan belonging to Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts was found submerged, upside down, in a narrow channel connecting Cape Pogue Pond with Poucha Pond at the eastern side of Chappy. In the car, rescuers found the body of a young woman, Mary Jo Kopechne, who had worked for the presidential campaign of the late Robert Kennedy the previous year.

With a group of friends and colleagues, Senator Kennedy and Ms. Kopechne had both attended a party at a cottage on Chappaquiddick the night before. Mr. Kennedy said he was intending to drive his guest back to the ferry before it stopped running at midnight when he took a wrong turn off the main road, drove down a long dirt road, and off the Dike Bridge into the channel. He failed to report the accident until the next morning, leaving behind a ledger of unanswered questions and mysteries that persist even now.

Overnight, the accident transformed Chappaquiddick. What had been an island that few beyond New England had ever heard of was now among the most discussed and investigated places on the planet. Like Watergate and its association with political scandal, Chappaquiddick became a byword for tragedy, intrigue, and dynastic upheaval. And for everyone associated with Chappy, whether from birth or by choice, the essential characteristics of the island – its isolation and disassociation from anything larger than itself – was, in a morning, forever lost.

Even so, the Chappaquiddick of today retains a full measure of its rugged outpost spirit and beauty. There is no place on the Vineyard as a whole – and by extension, no place on the globe – that resembles it.

Across the landscape and along the endless shoreline, visitors discover an astounding and diverse array of oceanfront and inland wildlife preserves, the largest owned and managed by The Trustees of Reservations, a state conservation agency, and others, just as memorable, by the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission. There are unmatched opportunities to angle for bluefish and striped bass up and down the ocean and outer harbor beaches. There are walking trails across Chappy that lead to vistas of startling beauty. And there is just one retail business, The Chappy Store (“A Tradition Since 8 a.m.”), which offers a few sundries to seasonal passersby and whose existence strongly suggests that, on Chappy, if the store doesn’t carry it, you probably don’t need it.

In one crucial, geographical way, Chappaquiddick today remains what it has always been: a destination, in many respects the final stop. The same sense of adventure that brings residents and visitors to the Vineyard in the first place inspires a certain percentage to go one island further. Chappy is not for everybody. It never has been. But those who really ought to experience it, whether as a resident or a visitor – well, one day, sooner or later, they always do.

Want to read more about Chappaquiddick? These two books offer detailed histories, both official and personal:

Chappaquiddick: That Sometimes Separated but Never Equaled Island, edited by Hatsy Potter (second edition) and Arthur R. Railton (first edition). Chappaquiddick Island Association, 2008 and 1981, Edgartown MA.

Pimpneymouse Farm: The Last Farm on Chappaquiddick, by Edo Potter. Vineyard Stories (2010), Edgartown MA.

http://www.mvmuseum.org/